Forty-five years ago this year, the beer that would inexorably change the drinking habits of America began arriving at bars and retail stores in select markets across the country.

In San Diego; Providence, R.I.; Knoxville, Tenn.; and Springfield, Ill., beer drinkers got their first taste of a new light, easy-drinking Pilsner that promised on delivering great taste with fewer calories than any other beer on the market at that time.

Two years later, in 1975, Miller Lite, the Original Light Beer, began rolling out across the nation. It was an overnight success, changing the way Americans drank beer.

Miller Brewing Co., Business Week magazine reported in 1976, “discovered a market that will be every bit as important to brewers as diet soda is to the soft drink industry.” The Milwaukee-based brewery’s introduction of Lite, it said, served to “accelerate a revolution that is changing the competitive framework of the beer business.”

Chicago roots

The story of Miller Lite, in many ways, begins in 1891 at the corner of North and Sheffield in that city’s Lincoln Park neighborhood.

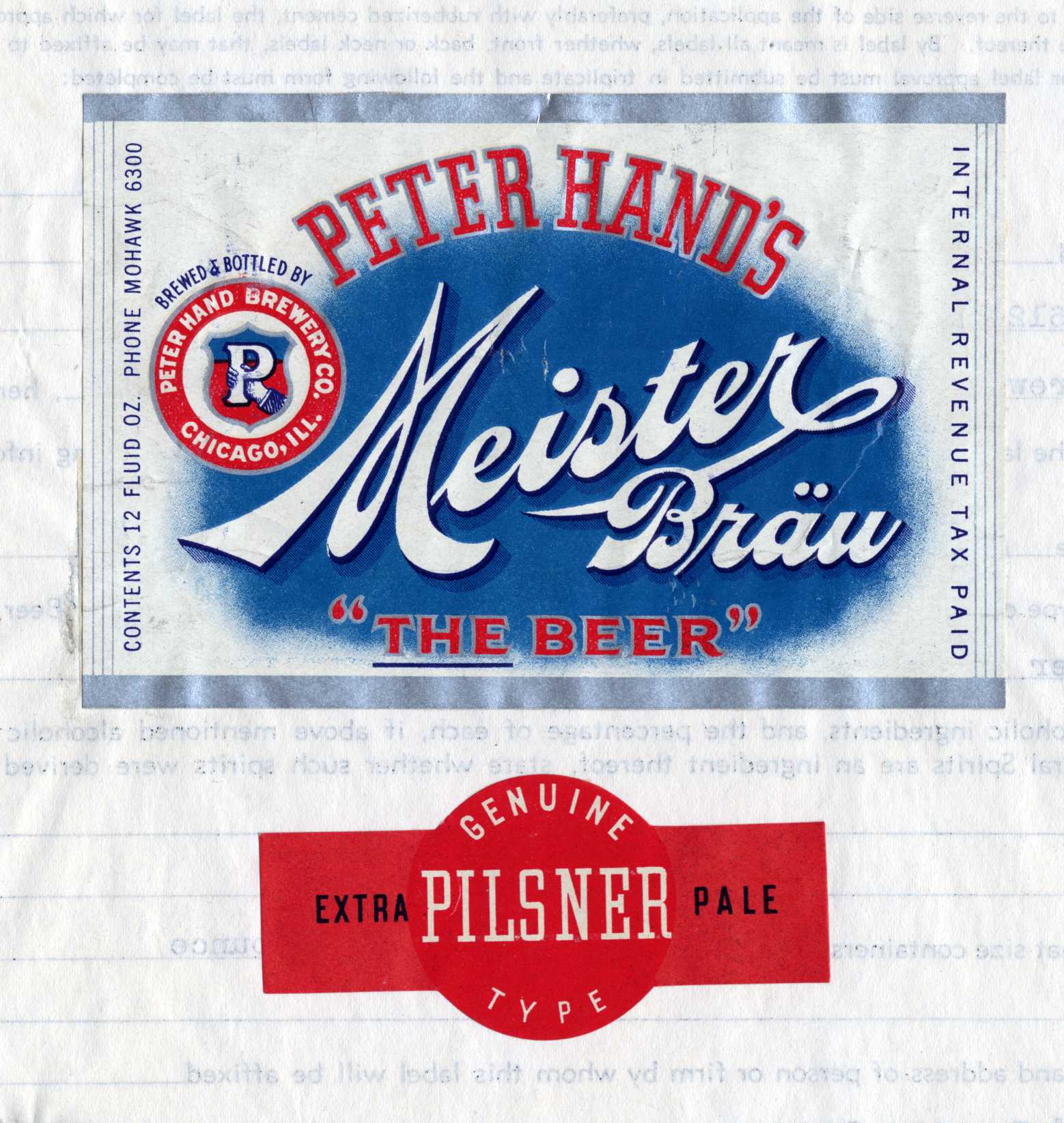

Today that corner is home to a shopping district surrounded by one of the city’s toniest neighborhoods. But 127 years ago — 20 years after a vast swath of the city was wiped out by the Great Chicago Fire — Prussian immigrant Peter Hand began brewing European-inspired beers to slake the growing thirst for beer in the booming city of more than 1 million.

Hand died in 1899, but his brewery survived, eventually becoming one of the largest in the United States.

And though his brewing career was cut short prematurely, Peter Hand’s name is etched into the history books for his introduction of the Meister Brau brand, a label that would more than a century later transform into the light beer known today as Miller Lite.

And though his brewing career was cut short prematurely, Peter Hand’s name is etched into the history books for his introduction of the Meister Brau brand, a label that would more than a century later transform into the light beer known today as Miller Lite.

Hand’s name is part of a sprawling list of relatively little-known players who played roles in the creation of what has grown to become the nation’s No. 3-selling beer.

Around the time Hand launched his brewing company, Chicago’s beer scene was booming. By 1894, there were 53 breweries in Chicago, third most in the country, despite the city losing more than 20 in the fire, according to Bob Skilnik’s “Beer: A History of Brewing in Chicago.”

The industry was brought to a grinding halt in 1919 because of Prohibition. Hand Brewing shuttered until the law was repealed in 1933.

After reopening, it expanded at a rapid clip, expanding several times, according to a “Lost Landmark” story from Chicago radio station WBEZ.

By 1965, the brewery employed nearly 600 people when it was purchased by a group led by investment banker James Howard. By the end of that decade, the brewery, then known as Meister Brau Inc., was making 1 million barrels of beer per year with annual sales topping $50 million, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. It was the 25th-largest brewery in the United States.

Its success was not destined to last.

'The Father of Light Beer'

Meanwhile, 800 miles away, an obscure biochemist named Joseph Owades was developing a “process to remove the starch from beer” and reduce its carbs and calories, according to his 2005 Washington Post obituary.

Owades, known by some as “the father of light beer,” studied fermentation science at Fleischmann's Yeast before beginning a long career at Rheingold Breweries in Brooklyn, N.Y.

“It was a common belief then that drinking beer made you fat,” he once said, according to his obituary. “People weren't jogging, and everybody believed beer drinkers got a big, fat beer belly. I couldn't do anything about the taste of beer, but I could do something about the calories.”

So came Gablinger’s Diet Beer in 1967.

“In America in the late 1960s, ‘light beer’ was pushed either as a vaguely medicinal (Gablinger’s actually had a picture of a doctor on the can) or something for the very diet-conscious, especially women,” New York Times Magazine reported in 2002.

The product flopped. But Owades did not give up.

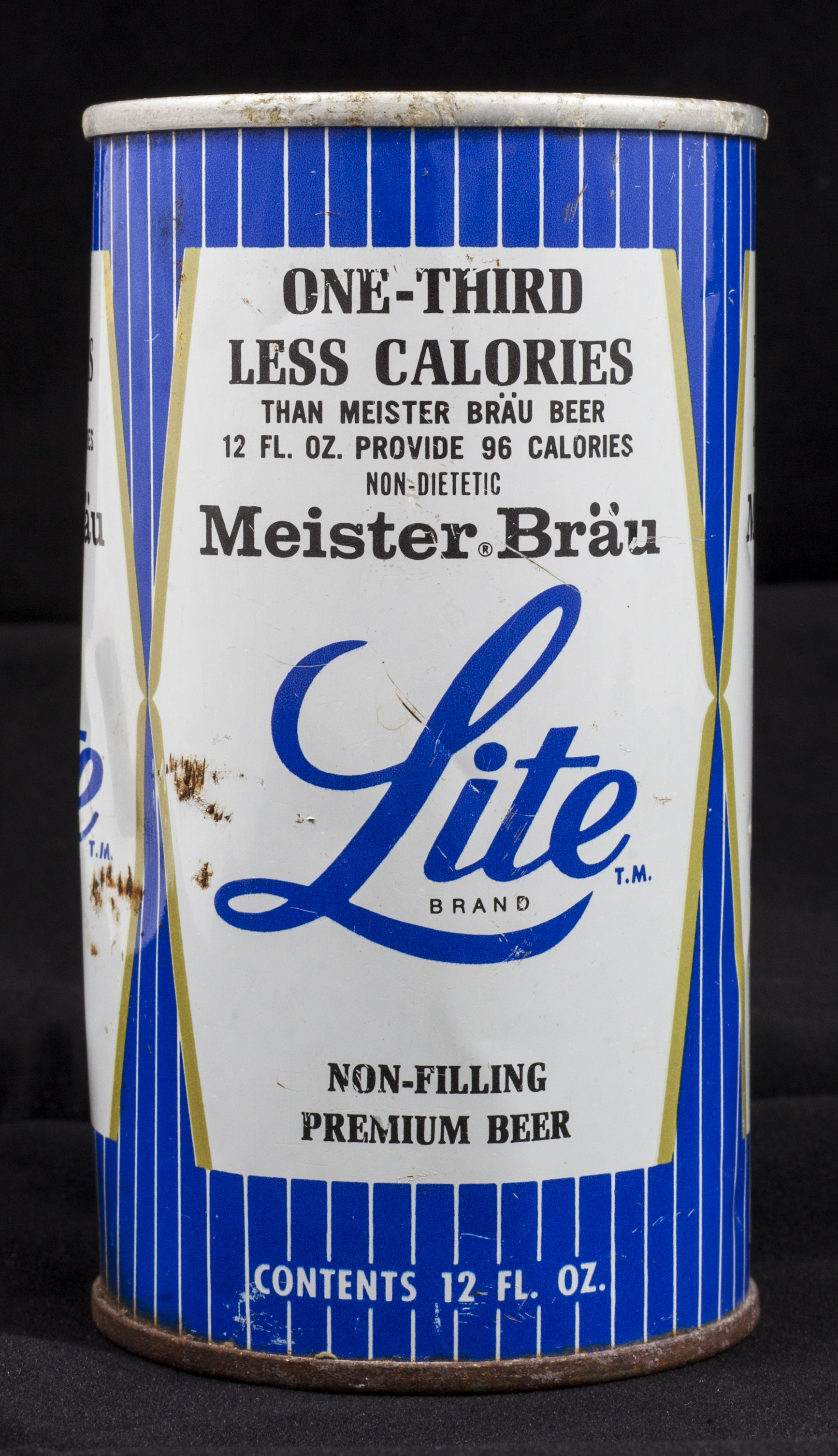

“With approval from his boss, Dr. Owades said, he shared his formula with a friend at Chicago’s Meister Brau brewery, which soon came out with Meister Brau Lite,” according to the obituary. “He routinely joked, ‘Being from Chicago, they couldn't spell ‘light.’”

Unlike Gablinger’s, Meister Brau Lite found early success.

“Chicagoans had accepted the Meister Brau line as their local beer,” Skilnik wrote in his Chicago history book. “The little neighborhood brewery had established itself as Chicago’s hometown favorite and a growing national brewery.”

From there, however, things began to unravel. And after a series of financial missteps, Meister Brau declared bankruptcy in 1972.

It sold its Meister Brau, Lite and Buckeye trade names to Miller Brewing in Milwaukee.

'There’s room for something like this in America'

Miller picked up where Meister Brau left off with Lite.

One inspiration for the brand may have been a trip John Murphy, then-president and CEO of Miller, and George Weissman, chairman of Philip Morris Inc. (the then-owners of the brewery), made to Germany in the early 1970s, according to the 2002 account in New York Times Magazine.

“Weissman was trying to keep his calorie intake down, and at a restaurant one night a waiter offered him a ‘Diat’ beer,” according to magazine’s account. “Murphy, an exuberant man of Irish descent, who was 6-foot-3 and weighed 250 pounds, didn’t exactly come across as a dieter himself, but he ordered one, too. The men sipped, Weissman recalls, and Murphy said, ‘There’s room for something like this in America.’”

The two went to work devising a strategy to bring the idea here.

“Murphy recalls summoning his brewmaster and telling him to come up with a light beer that had something that Lite at that time lacked – a beery taste,” according to a 1978 Esquire article.

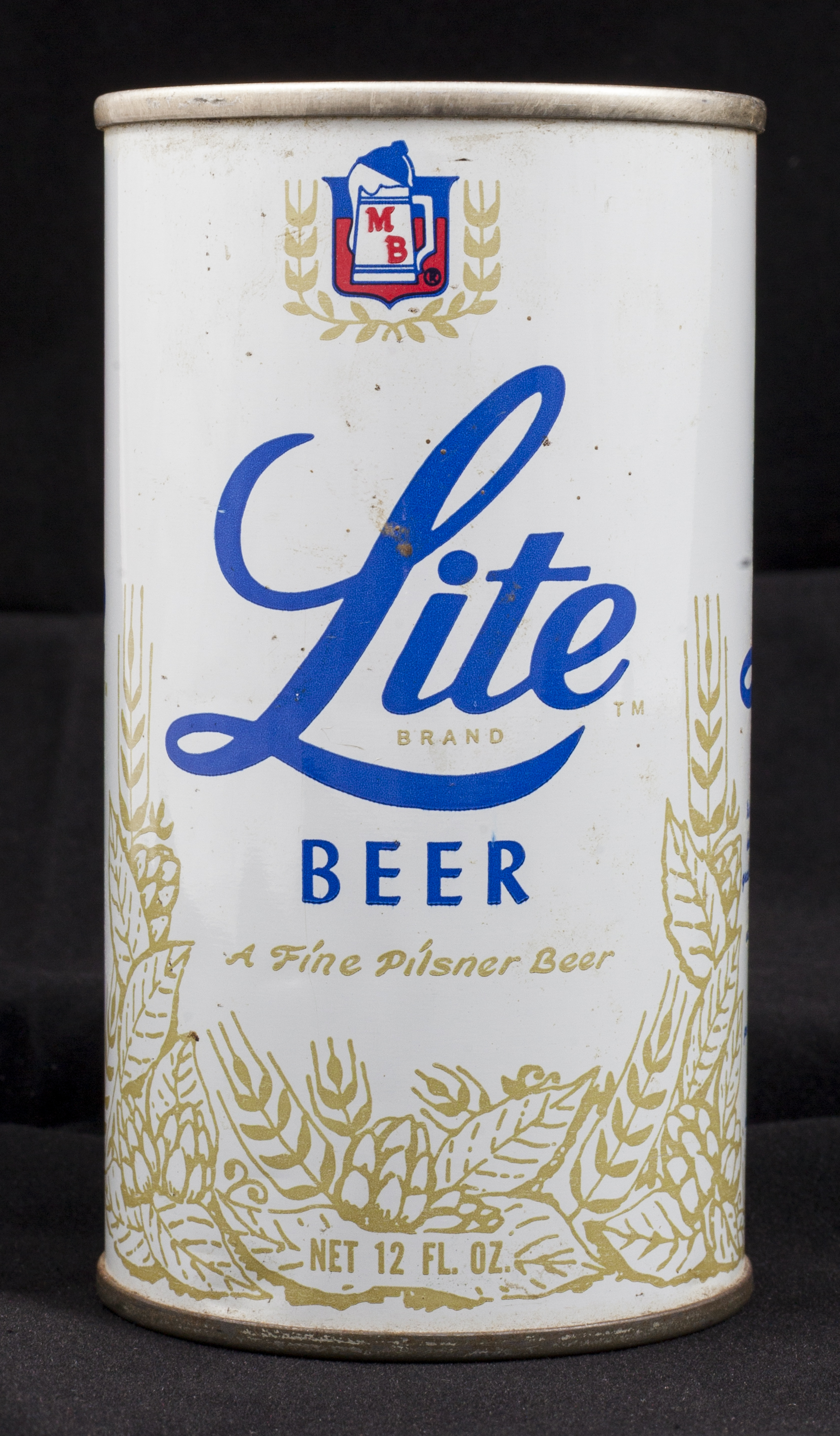

Indeed, “Meister Brau Lite was one of the first entrants in the low-calorie beer market, but Miller has since modified the beer’s formula,” according to a 1975 Business Week article.

The result: A recipe that “uses a unique blend of choice Saaz and Pacific Northwest hops and a significant amount of caramel malt,” brewed with the same strain of brewer’s yeast that Frederick Miller brought with him from Germany in the 1850s, the company says. That, and a brewing process focused on consistent quality, honed over more than a century of brewing in Milwaukee.

The result: A recipe that “uses a unique blend of choice Saaz and Pacific Northwest hops and a significant amount of caramel malt,” brewed with the same strain of brewer’s yeast that Frederick Miller brought with him from Germany in the 1850s, the company says. That, and a brewing process focused on consistent quality, honed over more than a century of brewing in Milwaukee.

And there was the packaging, which got its reboot from Walter Landor, a well-known graphic designer who had worked on several prominent Philip Morris brands.

After rolling out in a series of test markets in 1973, the beer returned to its birthplace of Chicago in 1974, a new look for the well-known Meister Brau Lite.

“Miller began saturating the Chicago daily papers with full-page ads and multiple thirty-second TV spots during local sportscasts, targeting the old Meister Brau and Meister Brau Lite crowd,” wrote Skilnik. “Lite beer from Miller, son of Meister Brau Lite, soon became the beer that made Miller famous.”

The beer that launched a new beer category

It was a story repeating itself across the country. The beer soon rolled out to more than a dozen other markets, and two years later, to a nation thirsty for light beer, kicking off a new category of beer that came to dominate beer sales in the decades since.

“Lite’s performance to-date in these markets continues to verify the strength of the brand,” according to a February 1975 internal newsletter announcing a national expansion. “Consequently, Miller feels that Lite is ready for the big time.”

American consumers were ready. But Miller initially was not. The brewery could not meet booming demand for Miller Lite.

“We could sell thousands more cases if we could only get them,” one unnamed distributor said in the 1975 Business Week article.

Lite vaulted Miller Brewing to the nation’s second-largest brewer in 1977, past the likes of Coors, Pabst and Schlitz. In 1972, it ranked fifth. Volume surpassed 31 million barrels in 1978, more than tripling from 9 million in 1974, according to Miller statistics.

The need to meet that demand almost single-handedly led to a more than $600 million investment in new brewing capacity across the country in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which included the addition of new breweries in Eden, N.C.; Albany, Ga.; and Irwindale, Calif.

Miller’s breweries were bursting at the seams to keep enough Lite in the market.

Ralph Rodriguez started work in shipping at the Fort Worth, Texas, Brewery as an 18-year-old in 1975, just as it was ramping up production of The Original Light Beer.

Ralph Rodriguez started work in shipping at the Fort Worth, Texas, Brewery as an 18-year-old in 1975, just as it was ramping up production of The Original Light Beer.

“I was excited to get on board. It was a big deal at the time. They were doing a lot of hiring. Everybody was excited about it. It was growing and growing and growing, and they just kept bringing people in. Miller Lite was taking off and kicking butt,” Rodriguez says. “It was 24-7, nonstop. We wouldn’t have any days off because of demand. And everybody liked it because it was growing.”

A novel approach to marketing

Lite took the industry by storm, in part because it took a novel go-to-market strategy that carved up the U.S. beer market into distinct segments and produced new products and packages for each, according to Business Week.

“Until Miller came along, the brewers operated as if there was a homogenous market for beer that could be served by one product in one package,” industry consultant Robert Weinberg, a former Anheuser-Busch executive, told the magazine.

A slate of smart advertising also helped. The Miller Lite All-Stars – a group of celebrity endorsers – and the “tastes great … less filling” campaign would come to define the brand for more than 15 years. It started with a $10 million blitz in 1975 – “the heaviest in memory for a new beer product,” according to Business Week.

Telling the story would be “convincing beer-drinking personalities” — as the brewery put it — like actors, actresses, comedians and retired athletes to get behind the beer and persuade other legal-age drinkers that they could drink light beer and enjoy it too.

In contrast to the first failed efforts to market light beers as “diet drinks to diet-conscious consumers who do not drink beer in the first place,” Miller found success with an approach offering “the big beer drinker an opportunity to drink as much beer as before without feeling so filled,” Business Week reported.

Embracing its Roots

That message remains core to the brand today.

And its roots are clearly visible:

The original design? Check. The brand in late 2013 revived its original can designs, sparking a surge in sales. Miller Lite continues to gain share in the premium lights segment.

Advertising focused on taste, calories, carbs and drinkability? Check.

Embracing its roots as The Original Light Beer? Check.

Celebrating its local roots? Check.

“Being the first, we take pride in that all the time,” Rodriguez says. “We said, ‘Hey, this is our beer.’ We were really proud of that. Family members, friends, acquaintances at the bar, it was a big deal. Everybody loved Miller Lite. To this day, it’s my No. 1 brand.”

Just as it is for millions of other Americans.